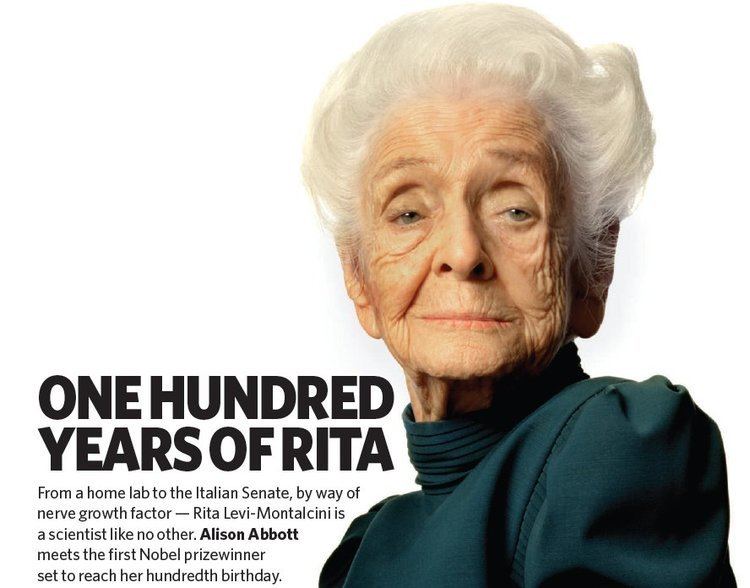

100 Years too Young - Remembering The Amazing Dr Rita Levi-Montalcini

Powered by RedCircle

The 2020 Nobel Prize in chemistry was a landmark event for women in Science as Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer A. Doudna became the first-ever only-women team to win a Science Nobel. This happened 120 years after the inception of the awards, showing how slow and hard it has been for women in Science. But women have won either solo awards (mostly peace and literature), or in teams with other male members. One such woman was Rita-Levi Montalcini, whose work and groundwork paved the way for all the future Biology researchers.

The life of science is difficult for everyone; it requires a passionate dedication and constant drive to learn and explore and invent. But like most walks of life, gender plays a huge role in women’s pursuit of knowledge. Even today, women constitute only 28% of all STEM workforce. When getting recognition and claiming a space for women is so hard today, imagine being a female scientist in the 1940s; even worse, being a Jewish female scientist during the peak of Fascism.

Rita-Levi Montalcini was an Italian neuroscientist. Born in 1909, she grew up in times of little peace and extreme conflict. Her struggle toward a life of science began at home. Rita’s father, who was a man of science himself, an engineer, did not want Rita and her two sisters to have a formal education. Such unfeminine pursuits would make her stray away from womanly duties like being a docile wife and a mother.

But long before the feminist movement would become mainstream, Rita knew such ideas needed to be killed before they could breathe. In an autobiography titled In Praise of Imperfection, she explained her views as, “My experience in childhood and adolescence of the subordinate role played by the female in a society run entirely by men had convinced me that I was not cut out to be a wife.”

With much struggle, she managed to get a seat in the University of Turin. Unbeknownst to them then, she was classmates with two future Nobel winners, Renato Dulbecco and Salvatore Luria. The three studied under neuro-histologist Giuseppe Levi and Rita graduated in 1936.

She remained attached with her mentor when she began her research with the nerves of chicken embryo.

My experience in childhood and adolescence of the subordinate role played by the female in a society run entirely by men had convinced me that I was not cut out to be a wife.

Contribution to the field:

Rita was fascinated by how a single cell divided and multiplied to create a billion, trillion celled organism. Even though this is basic biology, almost every middle-school student can recite how all of us begin a single gamete that fuses to become a zygote then an embryo and finally, a person.

But back then, little was known about how or why it happened or the exact mechanism.

When the anti-Semitic fever was surging through the country and bombs started to drop, she had to flee to the mountains in a cabin. Yet, she did not stop pursuing her research. She made a lab in her bedroom, acquiring equipment she could or fashioning them with whatever was available around her. She lied to local farmers and borrowed eggs to feed her hungry children (a lie towards a Noble cause, huh?). Those eggs became her valuable test subjects. She had to flee once more, as the Nazi troops advanced in their direction. This time, she settled up her lab in a basement in Florence.

By the time the war ended, the word of her work reached another embryologist Viktor Hamburger, who invited her to collaborate.

In the 1950s she successfully isolated a substance harvested from tumors in mice that caused vigorous nervous system growth in chicken embryos. Working with biochemist Stanley Cohen, she discovered Nerve Growth Factor (NGF), a protein essential for the survival of the neurons. This proved Hamburger’s hypothesis wrong (lack of differentiation among neurons).

In 1986, she along with Stanley Cohen were awarded The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. She was the fourth woman to win this honor.

Rita would go on to create many more landmarks with her passion for science and angst against Fascism. (Listen to Jamal and Megan to find out more). She lived to be 103 but she never married or had children. In an interview during her later years, she said, “My life has been enriched by excellent human relations, work and interests. I have never felt lonely.”

Rita was “wrong” for most people in her life. She was feminist in a family of orthodox, patriarchal hardliners. She was a Jew in Mussolini’s Italy where their very identity was a reason enough for eradication as human beings. She was a woman in a field fueled by testosterone. Yet, she persevered. Listen to our podcast to learn more about the fascinating life led by a feminist science pioneer and honor her legacy.

Powered by RedCircle